Should Citi Bike Expand Across The Hudson?

In February 2014, Hoboken, Jersey City, and Weehawken announced plans to jointly launch a bicycle share system using bikes from Nextbike, a German company that operates bike share systems in Germany, Austria, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Hungary, Latvia, New Zealand, Poland, Switzerland, Turkey, the United Arab Emirates, and the United Kingdom.

In June 2014, the Wall Street Journal reported that the plan faced delays:

Potential sponsors apparently grew skittish in the wake of publicity surrounding financial troubles facing New York City’s bike-share, which is the country’s largest, the officials said. The bike-share’s initial costs were estimated to run about $2.5 million.

On September 27th, 2014, Matt Chaban reported in the New York Times that Jersey City plans to opt out of the three-city system in favor of expanding Citi Bike across the Hudson. Jersey City mayor Steven Fulop told Chaban:

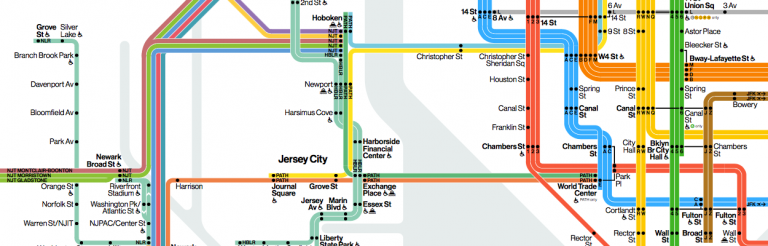

“What’s most important for me is that folks in the Heights or Greenville,” two of the city’s neighborhoods “where there’s not great access to the PATH, can get to the train, get out on the other side and then get on a bike,” he said.

If Jersey City is opting to join the nation’s largest bike share system and expand it outside the boundaries of New York, should Hoboken and Weehawken follow suit?

Several other cities have built regional systems that include adjacent municipalities, including the nation’s second-largest system in and around Washington, DC. Capital Bikeshare has stations located outside the DC limits in Alexandria, Virginia, Arlington, Virginia, and Montgomery County, Maryland. Boston’s Hubway includes the adjoining cities of Brookline, Cambridge, and Somerville. On the west coast, Bay Area Bike Share has stations located throughout San Francisco and the nearby cities of Mountain View, Palo Alto, Redwood City, and San Jose.

To build a successful bicycle share system, there are three possible sources of financing: public funds, ridership revenue, and corporate sponsorship. All three systems noted above make use of public funds for infrastructure. Each participating municipality invests a fixed amount of money to buy and install bikes and docking stations. A private firm is contracted to handle day-to-day operations and share revenue with the public partners. Corporate sponsorship introduces a third source of funding in return for naming or other marketing opportunities, but of the three systems mentioned, only Boston has a corporate name sponsor: New Balance. In DC’s case, its ability to enter into advertising agreements is limited by a longstanding memorandum of understanding with the Federal Highway Administration that bans outdoor advertising on fixtures in public space. Violating that MOU could result in the loss of federal funding. In the Bay Area, the urban planning and good-government organization SPUR published What Bay Area Bike Share Will Need to Succeed. It argues that corporate sponsorship is a necessary complement to public investment for future expansion, but that the system needs to maintain a single, recognizable brand:

- We need a longer-term source of funding to grow this program. This could be either a single corporate sponsor for the entire region or multiple local sponsorships. We’re not sure which is more likely, but think both are worth pursuing.

- Even if there are multiple sponsors, we think the program needs to keep its unified regional brand. Our region has learned the hard way the challenges of a highly fragmented transit system with 27 different operators (each with separate fares, schedules and maps). We believe bike sharing will be most successful if it retains one regional fare, and one recognizable brand, throughout the Bay Area.

Boston uses all three financing tools, while the Bay Area and DC use two: public investment and ridership revenue. By contrast, Citi Bike is the only bike share system in the US to operate without any investment of public funds, so it is heavily reliant on a $41 million sponsorship from Citibank, and private capital invested by Alta Bicycle Share, the company managing the system. Since Alta primarily generates revenue from management of Citi Bike and other systems around the country, that revenue is dependent on usage of bike share. Strong adoption of Citi Bike by riders purchasing annual memberships resulted in record ridership in the months after the system opened, as seen in this visualization of rides taken over a two-day period in September 2013:

However, those annual memberships aren’t a high-profit revenue source. Also, problems with the payment software used in station kiosks resulted in lower-than-expected sales of the higher-profit daily- and weekly-passes that would fund expansion of the system. That has led to much-publicized financial problems for Alta, a long stall in Citi Bike growth, and reticence among potential corporate sponsors for the proposed Hoboken-Jersey City-Weehawken system.

Like Citi Bike, the Hoboken & Weehawken plan is completely reliant on private financing, but the potential for logistical problems of the type experienced by Citi Bike are mitigated by the smaller size of the system (300 bikes vs. 6,000 in New York), and lower cost per bike ($1,200 vs. $5,000 for the Bixi-manufactured bicycles used in the Citi Bike system). The Hoboken & Weehawken system is set to launch in November, whereas Chaban notes that Citi Bike expansion to Jersey City might take place by May 2015. Hoboken is seeking public input on station locations, and intends to have bike share stations located throughout the city, whereas the logistics of a Citi Bike expansion to Jersey City are unclear. Although the Hoboken & Weehawken system will require a separate membership from Citi Bike, Hoboken Mayor Dawn Zimmer noted to Chaban that integration with Citi Bike might be a possibility in the future:

Ms. Zimmer said she had no regrets about how things had developed. “I hope we can integrate with Citi Bike someday, but launching was more important,” she said.

Kim Velsey, senior editor at the New York Observer, asked in a recent article whether it’s time for New York to make Citi Bike a real part of the transit infrastructure:

Given that the government subsidizes roads, highways, trains, subways, buses, ferries and even airlines, it’s unclear why bicycling should be the one exception, especially when its costs are so low compared to other transit systems. (Especially ferries.)

Investment of public funds to purchase and install bikes, stations, and infrastructure would be a logical fix for Citi Bike’s growing pains, but public funding comes with its own set of complex issues. Controversy can ensue when the idea of spending public dollars on one project is seen as taking away from another. It can take longer to identify sources of public funding, and competition for limited dollars is often intense. There is also no guarantee that even a thoroughly developed, obviously strong idea will find enough funding to move from concept to reality. Privately-funded projects are therefore attractive to political leaders because the announcement of a project that will benefit the public, but requires no public investment, is sometimes seen as an easier route to completion. It also makes for a better headline, especially among constituents who don’t pay close attention to the political process.

Since Jersey City has opted to go with Citi Bike, expansion across the Hudson could be an ideal way to test a public-private funding scheme similar to the approach used in the Bay Area, Boston, Washington, and other cities. Jersey City could seek grants from agencies like the Federal Transit Administration, which provided funding for Boston’s Hubway and Chicago’s Divvy, and the New Jersey Transportation Trust Fund, in addition to private-sector sponsors. Alta, Citi Bike’s operator, could use what it learned when it recently landed a five-year, $12.5M sponsorship deal with Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Illinois to support the expansion of Chicago’s Divvy bike share. The North Jersey Transit Planning Authority (NJTPA), the federally authorized Metropolitan Planning Organization for the region, could help coordinate the expansion, just as the Boston Metropolitan Area Planning Council did for Hubway. If the approach is successful, New York and New Jersey officials could use it as a blueprint for investing public funds to further expand the system.

Hudson County’s recent population growth has been driven by New Yorkers who are willing to look west of the Hudson for housing options that generally offer more space at slightly better prices, but are just a subway stop or two outside Manhattan on the PATH train. A Citi Bike presence west of the Hudson would give people who are already familiar with it another reason to use an expanded network that’s available on both sides of the river. So should Citi Bike expand across the Hudson? The easy answer, on paper, is yes. But given the current situation, Hoboken and Weehawken seem to have a more feasible plan that gives the greatest number of residents access to bike share in the shortest amount of time.