A Viable Plan for Penn Station

At the 2014 Summit for New York, the Municipal Art Society and Regional Plan Association presented the latest development in their Penn 2023 campaign to remake Penn Station. The 42-page report, Madison Square Garden: Shaping the Future of West Midtown, highlights two options for the future of the station and arena, along with a feasibility study for turning the surrounding neighborhood into a cultural district. The first option, presented as the ideal scenario, would relocate Madison Square Garden one block southwest, replacing the Morgan postal facility on a site bounded by Ninth and Tenth avenues between 28th to 31st streets. Without the arena above it, Penn could rise above street level, restoring a semblance of what was lost when the original was demolished in 1963.

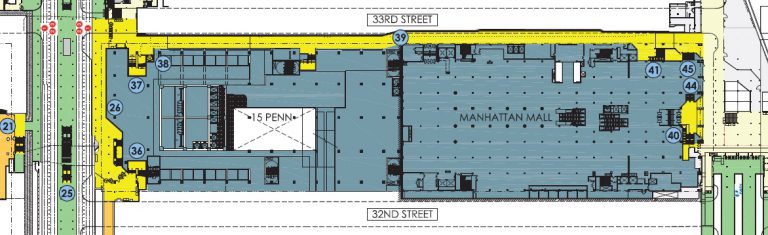

A second option, developed by architecture, design, and consulting firm Woods Bagot, was presented as the backup if the first option’s “grand bargain” to move MSG can’t be reached. It focuses on reconfiguring the complex at street-level to create an entrance hall for Penn Station. Woods Bagot’s website says the proposed hall would be as large as the main concourse of Grand Central Terminal, contain retail and dining, and extend around the arena to the station’s Seventh and Eighth avenue entrances.

Director Jeffrey Holmes discussed removing the theater that sits under MSG on the Eighth Avenue side and opening up that facade to be a big entrance hall with steps down to the concourses. The floor of the arena, which is currently elevated, would serve as the hall’s ceiling. A similar move could apply to Seventh Avenue, resulting in a more prominent entry hall there, too, which would “open up the center of the site” and bring light down to the concourse level.

The multi-level, glass-enclosed expansion flows around the arena and 2 Penn Plaza tower, framing a second, east-facing entry hall on Seventh Avenue and bringing street-activating retail and dining to the block’s north and south edges. The four-story-tall expansion mirrors the civic scale of the Farley Post Office, recalling the cornice line of the historic Pennsylvania Station, and supports a new rooftop public garden. The arena, which gains additional program space as part of the expansion, is clad in reclaimed timber to complete the “new” Garden.

The proposal is similar to a 2008 idea from Vornado Realty Trust CEO Steven Roth, also presented as an alternative to a full-scale relocation of MSG:

We have with Madison Square Garden a Plan B, which is they stay where they are, we take out the theater, we—underneath the seating bowl of the arena—put a new grand entrance to Eighth Avenue and a new grand entrance to the station on Seventh Avenue, and what that will do is create a grand train station. Not quite as grand as moving it, but pretty nice. Actually, spectacularly nice.

The “grand bargain” proposal to move Madison Square Garden and rebuild Penn without the arena above it is visionary, but a brand-new, above-ground station building doesn’t fix the most urgent issues with Penn Station. Worse yet, it could divert attention and resources from them at a time when the region can’t afford to wait. The century-old North River Tunnels are already operating over capacity, and the brackish water that inundated them during Hurricane Sandy has caused deterioration that may force Amtrak to shut them down for repairs. Any disruption in service to the only intercity rail tunnels connecting New York and New Jersey would be felt along the entire Northeast Corridor, from Boston to Washington, and as far west as Chicago.

Furthermore, Penn station itself is trifurcated into three separate passenger environments, which inhibit smooth passenger flow, complicate transfers between Amtrak, Long Island Rail Road, and New Jersey Transit, and make an already limited underground space even more congested and unappealing to travelers. As the new towers at Hudson Yards open over the next five years, their residents and workers will put additional strain on the existing station and tunnels, long before the vision of a new Penn Station is realized. These problems are too critical to wait for the “grand bargain” to become reality.

Woods Bagot’s – and Roth’s – proposal, by contrast, appears significantly more feasible and politically practical. It would address several of the station’s most critical needs–street presence, passenger flow, lighting, seating, and access to tracks–in a much shorter timeframe, and at lunch lower cost, than relocating the Morgan postal facility, building a new MSG, and demolishing the current arena, just to reach the point where a new Penn could be built. It would also be more palatable to the Madison Square Garden Company, because it preserves the $1B invested by the company between 2010-2013 to modernize The Garden.

MAS and RPA’s successful 2013 campaign to limit The Garden’s operating permit to ten years put its owner on notice that staying put wasn’t a given, and was a major victory for political awareness of the critical problems surrounding Penn Station. Now it’s time to use the leverage gained from that victory to engage MSG, city and state politicians, and the three transit agencies that occupy Penn to make the Woods Bagot proposal and Amtrak’s Gateway tunnels a reality well before 2023.