Chapter 1: Grassroots is Best

Wikipatterns – Table of Contents

In the Ford plant, Toyoda saw that the sheet metal parts needed for car assembly were produced using an expensive die stamping system that produced massive quantities of parts which were stored in warehouses until needed on the assembly line. When the system produced parts with defects, they were set aside to be repaired later, adding more time and expense to the manufacturing process. (Ensici, 2006) Toyota didn’t have enough money to maintain a system this complex and Toyoda felt it could be made more efficient, so he enlisted the help of Taiichi Ohno, an engineer and machine shop supervisor whose work is now recognized as critical to developing the processes that anchor the famous Toyota Production System. (Toyota Motor Manufacturing Kentucky, 2006)

It was on this assignment that Ohno made some critically important discoveries about the role of community and collaboration in improving manufacturing. He concluded that it was better to produce small batches of parts – just enough to cover assembly line needs for the day – because it eliminated storage costs and allowed workers to find and correct defects faster.

But to make this system work at all (a system that ideally produced two hours or less of inventory), Ohno needed both an extremely skilled and highly motivated work force. If workers failed to anticipate problems before they occurred and didn’t take the initiative to devise solutions, the work of the whole factory could easily come to a halt. Holding back knowledge and effort – repeatedly noted by industrial sociologists as a salient feature of mass production systems – would swiftly lead to disaster in the Toyota plant. (Ensici, 2006)

Ohno’s solution was to create small groups of workers, and have them work collaboratively to find the best way to work on their assigned part of the assembly. Instead of the hierarchical system used in mass production where only the foreman had control, each worker was given the power and responsibility to stop the production line if an error was found.

By rapidly eliminating the source of the problem, errors did not propagate and multiply through the system as cars moved down the assembly line. In comparison with mass production, as a team of workers becomes more and more accustomed to lean production, the amount of rework required is slashed dramatically. (Ensici, 2006)

So why is this story relevant almost sixty years later? What Toyoda and Ohno did all those years ago transformed Toyota from a small, local automaker into an industry legend that has dominated the global auto industry for decades. By creating a system where every worker had the power to stop the assembly line if they found a problem, the system instilled greater individual responsibility, and gave workers a more direct stake in the success of their work. But even more importantly, the system relied on collaboration among small groups of people to find the best way to do the job, and this is profoundly important.

Instead of giving people a job, and trying to control how they work, it’s better to let go: give them the job, and let them figure out the best way to do it. That’s the principle that guided Ohno and Toyoda, and it’s the same principle that guides wiki use.

The outcome is what matters, not the method.

Not only is the end result better, but it’s not just a flash in the pan. It’s something sustainable. And isn’t that what every organization wants?

When groups work together to find the best way to get a job done, the high quality of work is sustainable because they’re finding out the best about themselves, combining individual complimentary strengths and talents, and refining their methods at a very high level. Because they control how they work, people are more self-reflective, constructively critical of their own work, and motivated to make the best contribution possible because they take greater pride in the quality of their work.

So what’s the problem?

Collaboration is more important than ever to the success of organizations, growth of economies, and solving some of society’s most complex problems, but the knowledge tools in use today fall short of these goals because they don’t let groups efficiently work together, are too structured, and are built around a hierarchical, command-and-control structure.

Take email, for example. It’s the most ubiquitous tool in organizations, and is often used to send a document around to a group for collaborative editing. Since the document is sent as an attachment, each person makes changes to a separate copy of the document, which means that at some point some really tedious work is required to assemble all the separate edits into one copy of the document. Never mind the mechanical issues, just think of the political issues that can arise if people have differing viewpoints.

Also, errors made by one person might propagate in a document that’s emailed around to each collaborator, and might not get fixed until the person who has to combine edits either finds the error s or is made aware of them. Worse yet, the errors might get fixed in some copies, but not others.

This is a nightmare that happens every day in organizations, and the deeper effect is it drives people apart. There’s more incentive to dig in your heels and fight for your viewpoint to be preserved in a document you edited in isolation, and so groups have a much harder time achieving cohesion and a strong mutual desire to produce the highest quality work.

Wiki?

Unlike email, which “pushes” discrete copies of the same information to each person, and then requires that the separate revisions be somehow combined, wiki “pulls” people together to work on the same text. Instead of separate copies for each person, everyone looks at the same text on a page, and can immediately make changes directly on that page. Everyone else can see those changes as soon as they’re made, which allows each person to better take others’ contributions into account as they edit. It also means that information gets created faster because the technical barriers – like downloading an attachment, opening it (and having the right software to do so!), then reattaching it to email and sending it on to other collaborators – are minimized.

Errors can be fixed immediately by anyone who notices them, and differing viewpoints can be worked out in a more natural manner. People can work together to reach a balance of viewpoints through a dialog that takes place as they edit, instead of putting forth versions that each feels is final.

The wiki is rapidly growing in name recognition and use in organizations because its simple design and function enables equal participation by people at all levels of technology knowledge and savvy. On top of that it has an unprecedented ability to adapt to different uses, bring people together and strengthen teams, and promote a collaborative approach to problems.

A wiki is simply a website in which users can create and collaboratively edit pages, and easily link them together. The basic idea behind a wiki is that anyone who can view a page can just as easily edit it and save their changes. Enterprise wikis build on the basic wiki idea by including certain functionality that meets the needs of organizations, such as the ability to easily create and manage many individual wiki sites for teams, projects, and departments. Enterprise wikis also include strict security to protect confidential information, fine-grained permissions so that people can be given access to appropriate spaces and pages, and can be tied to other enterprise services via LDAP authentication and single sign-on. These features enable the wiki to mimic the existing social and organizational patterns in departments, teams and projects.

The first wiki, WikiWikiweb, was created in 1995 by Ward Cunningham to document and collaboratively update information on software design patterns. Since then, wiki has grown steadily into one of the most important tools in today’s enterprise, and has become a fixture in popular culture thanks to the rapid rise and increasing influence of Wikipedia. It’s commonly thought of today as a so-called Web 2.0 tool because of it’s proximity to blogs and social networks, but this is primarily because its popularity and name recognition has taken off in tandem with the Web 2.0 phenomenon.

Wiki is the Hawaiian word for quick. According to Cunningham, he chose the word WikiWiki, or Wiki (short version), to describe this new tool after remembering that a counter agent at Honolulu International Airport had directed him to take the wiki wiki bus to travel between airport terminals, and had explained that wiki is the word meaning “quick” in Hawaiian. (Cunningham, 2005) According to Cunningham (2005), “I wanted an unusual word to name what was an unusual technology. I was not trying to duplicate any existing medium, like mail, so I didn’t want a name like electronic mail (email) for my work.”

The Wikipedia Factor

For many people, the first exposure to a wiki is Wikipedia and this creates misconceptions about what a wiki is and how it can be used. One common misconception is that it can only be used as an encyclopedia. There’s a major fear about privacy of information, or the perceived lack thereof in wikis, since Wikipedia is a completely open wiki where anyone can see any page, even without logging in. Security and integrity of information is another big concern. Because Wikipedia resides on the open Web, people assume that if they used a wiki for internal collaboration anyone could change the information on any page, even if their edits result in inaccurate or completely erroneous information. The reality is quite different when a wiki is used inside an organization, and I’ll explore these issues in the next chapter.

You Can Do It!

Because it’s a different kind of tool, the early adopters and Wiki Champions – those that already see its potential and want to bring it to fruition on their organizations – can benefit from applying the best strategies for educating others and growing wiki use. This book, and the companion wiki site Wikipatterns.com, provide a toolbox of strategies in the form of patterns and anti-patterns, guidance on the stages of wiki adoption, and suggestions on what patterns to apply along the way.

Any grassroots, or bottom-up, strategy is the best place to start since the success of a wiki depends on building active, sustainable participation and this only happens when people see that the software is simple enough to immediately be useful, and meets their needs without requiring them to spend lots of extra time.

A good first step is to identify a group or department who would likely benefit the most from using a wiki, and whose people are open to trying new tools. If you’re looking to expand wiki use in another group, look for the thought leader in the group – someone who is very forward thinking, respected by peers, and willing to champion a new idea and get others around them involved.

If you’re the thought leader and wiki champion, congratulations! Encouraging others to use a wiki can be as easy as the wiki itself if you encourage the right patterns of behavior and content creation. Read on for more ideas, and feel free to add your ideas and strategies to this wiki as well!

Unleash the Early Adopters

Put a wiki into your environment, and you’ll probably only have to ask others to use it once (maybe twice). After getting the hang of it and finding that it becomes essential to their work, users become the new wiki coordinators themselves. Often they’ll do your asking for you by asking their peers to participate too. Volunteers are your champions, you just need to give them a nudge!

A wiki has the best probability of success when it gains grassroots support, and people respond well when they see peers actively using and evangelizing it. Don’t mandate wiki use; make it available, then let people find where it’s most useful to their work. If they find a new way of doing something, embrace it with an open mind. It may just be an incredibly valuable improvement.

Let people find their natural roles. Some may be interested in gardening the wiki, i.e. maintaining and organizing the site; others may want to help grow its use. By letting people lead wiki growth and feel a genuine sense of ownership over their work, you’ll be laying the foundation for it to become a successful collaboration tool.

Move Swiftly and with Purpose, but Don’t Rush It

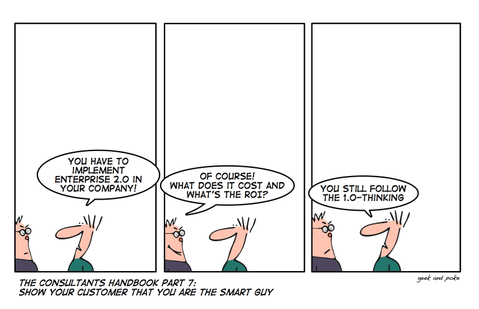

One of the biggest mistakes an organization can make is to ignore enterprise 2.0 and its value, but an equally dangerous mistake is to rush into things and forget to give people time to adjust to the new ways of working with tools like wikis. It takes time to gather content that’s spread around in disparate places and gradually move it to a wiki, and simultaneously shift existing practices like collaboration over email to wiki based collaboration.

Be patient when you introduce a wiki to your organization. Some of the payoff won’t be immediately apparent because it takes time for people to change the way they work, so it’s more important at the beginning to focus on getting broad support and organic growth from all across the organization. Once people see that wiki collaboration actually replaces less effective uses of other forms of communication, like trying to collaboratively edit a document via email, and gets things done faster, growth will follow.

Using a wiki doesn’t mean you have to abandon the tools you’re already using. Trying to replace everything else too quickly with the wiki might lead to its downfall if it’s not the right solution. It takes time for people to get used to the wiki and find the best uses for it, so when you make it available let it work alongside everything else. Find ways to blend it with what you currently do (example: some tools let you subscribe to an RSS feed or email update on changes to the wiki), and it won’t feel like yet another thing clamoring for your attention.

It Doesn’t Matter Where You Are

At Atlassian, we have offices in Sydney, San Francisco, and Kuala Lumpur, and one wiki for everyone. This makes it easier to put information in one place where everyone has access and the ability to offer input. For a global company, we’re all in close touch and able to communicate, make decisions, and work across these great distances very quickly. The general idea here is that no matter where in the world you’re based, the wiki doesn’t just have to be used by people in close proximity to each other – it can bring those who are far away much closer together, to everyone’s benefit.

Listen

Most enterprise collaboration and knowledge management software is geared to only the functions necessary to the bottom line. This makes it attractive to the bean-counters but not to the people who will actually use it. Here again, the wiki is different because of the absence of rigid structure – besides just having wiki pages for project, meetings, and so on. people can also have pages for personal profiles, blogs, even to organize a lunch outing! These pages are a gold mine for people’s ideas, opinions, and progress on their work. You’ll probably be better informed about your people & projects than ever before, and you can offer feedback which shows them you’re listening and taking them seriously.

Furthermore, profile pages can be useful as a standard place to find contact information, people’s biographies (for leadership and public facing employees this is a great way to always have the most up to date bios for trade publications, conferences, etc.), and can be a great place for them to keep links to the project pages they’re working on.

Embrace Emergent Behavior

Renegade thinking is critical to success, but most often the tools an organization selects can spur or damper thinking. The wiki allows for informal, unstructured collaboration, where right-brain thinking thrives. It does away with the rigid structure in a lot of other collaboration and knowledge management tools, and lets people use it as they see fit. There’s room for greater innovation, and if the wiki is brought in by renegades, then it’s very likely that its success will have much to do with their enthusiasm for it.

In the same way that a wiki is the means to collaboration, it could also be viewed as the product of collaboration. What about using a wiki as your website? The point being, what a wiki is and how it’s used are as much about breaking the rules as it is defining new rules.

Become Better at What You Do

Alan Kay, the visionary genius behind the graphical user interface, smalltalk programming language, and ARPANET – the predecessor of the Internet – was recently interviewed by CIO Insight magazine. In the interview, he discusses what isn’t right about personal computing and how we should change our thinking for the next generation of computing. From the interview, entitled “Alan Kay: The PC Must be Revamped–Now”:

“Engelbart, right from his very first proposal to ARPA (Advanced Research Projects Agency), said that when adults accomplish something that’s important, they almost always do it through some sort of group activity. If computing was going to amount to anything, it should be an amplifier of the collective intelligence of groups. But Engelbart pointed out that most organizations don’t really know what they know, and are poor at transmitting new ideas and new plans in a way that’s understandable. Organizations are mostly organized around their current goals. Some organizations have a part that tries to improve the process for attaining current goals. But very few organizations improve the process of figuring out what the goals should be.”

As I read this, I realized that it’s a brilliant argument for why the wiki can be a vital tool for organizations. Because it doesn’t define the terms of interaction and collaboration from the outset, and allows structure to be created, modified and removed as needed, the wiki quickly becomes a desirable tool because it “learns” how people work _as_ they work, not after the fact. This means it captures more of the actual process, giving them an opportunity to regularly look at how they collaborate, even during a current project.

Think how much more productive a group can be if it sees where it’s weak during a project and can correct that weakness on the spot. Now imagine how much more productive an entire organization can become if every group is doing this. Toyoda and Ohno realized this, and didn’t just look at how things fit into the assembly line, but thought in terms of the whole strategy. That enabled them to create a whole new way of working that engaged employees, involved their thinking skills instead of just their manual labor skills, and resulted in stronger employee loyalty, lower storage and repair costs, and some of the best products in their industry. You can do the same for the knowledge in your organization using wiki collaboration – that’s the promise of collective intelligence realized!

Wikipatterns Directory

Human behavior is pattern-based, and wikis are designed to support the patterns of activity that occur when groups work together. Since patterns describe how people already behave, documenting and applying them can help guide future behavior. That’s why we created the Wikipatterns directory. It’s organized around three major strands of content:

- People patterns and anti-patterns

- Adoption patterns and anti-patterns

- A look at the stages of wiki adoption

The patterns and anti-patterns are loosely modeled on the concept of software design patterns — those recurring patterns of behavior that can be recognized and channeled for the good of the team. Patterns are the types of activity that one would want to happen on the wiki, and anti-patterns are the scenarios that should be avoided or fixed to keep the growth of wiki use on track. For instance, the IntentionalError pattern suggests making an obvious mistake that someone else will be so compelled to fix, they just jump in and do it – and they’ve edited the wiki! The idea here is that a person’s primary motivation when they see an error is to fix it, and the wiki provides an easy, immediate means to do so.

What has worked for you? I’d love to have your thoughts on this. So I invite you to look through the patterns, see which ones you may have used, and contribute examples, anecdotes, tips, or whatever else you think is important. I hope that you’ll also find useful patterns to use in your own wiki work, and will contribute ideas and feedback after you’ve tried using those patterns.

References

- Alter, Alan. Alan Kay: The PC Must Be Revamped—Now, CIO Insight, 14 February 2007 (Retrieved 24 May 2007).

- Cunningham, Ward. Correspondence on the

Etymology of Wiki, February, 2005 (Retrieved 25 July 2007). - Ensici, Ayhan. Frog History Lessons, Designophy, 19 October 2006 (Retrieved 8 May 2007).

- Toyota Motor Manufacturing Kentucky, Inc. “History”, Toyota Motor Manufacturing Kentucky, Inc., 2006. (Retrieved 24 May 2007).